Blueberries as Ornamental Edibles

Blueberries are a great candidate for container production. They fit into the ornamental edibles market niche and combine consumer interest in edible gardening, sustainability and low-care perennials. Blueberry cultivars selected for local conditions can be planted out into the environment as a perennial landscape plant, enjoyed as patio potted plants, and have multi-season interest with spring to summer blooming, fruiting, and foliage, and fall color.

The University of Florida (UF) is currently researching container blueberry production in collaboration with growers in the Young Plant Research Center group (www.floriculturealliance.org).

Flowering and Fruiting Cycle

Flower initiation, dormancy and chilling processes in blueberry (Vaccinium) are similar to florists’ azalea (Rhododendron, also in the Ericaceae). Blueberries initiate flowering naturally in the fall (September to November) under short days and cool night temperatures (Figure 1). In most locations, this is followed by a “dormant” cycle with cool winter temperatures. During the dormant period in late fall, active growth ceases, leaves turn red and may then fall off. After the plant becomes dormant, a cultivar-dependent chilling period (between 32 and 45° F) of roughly 200 hours (Southern cultivars) to 1,000 hours (Northern cultivars) is required to break dormancy.

After chilling and under the longer days and warming temperatures of spring, the plant begins to grow actively again, with a flush of leaves and vegetative shoots, and development of flowers. Fruit set occurs following pollination by insects such as honey bees. Green fruit typically appear four weeks after flowering, and ripe fruit nine weeks after flowering, but this varies considerably with cultivar and temperature. Flowers contain both male and female organs, but growing a mix of cultivars for cross-pollination significantly increases fruit set. Flowering is variable between plants, meaning that if marketing plants in bud or fruit, they need to be hand-selected from the bench.

Plants can also be grown under warm conditions without dormancy or chilling requirement (termed “evergreen” or “non-dormant” production, Figure 1). The flowering period for evergreen production tends to be more extended and less intense than for plants grown with a dormancy cycle. In Florida, this evergreen cycle naturally occurs during warm winters with Southern highbush cultivars. However, evergreen production is unlikely to be useful for northern growers in heated greenhouses, because evergreen flowering on Northern cultivars tends to be weak, flowering occurs too early (for example, December/January), and without pollinating insects the flowers will mostly senesce and fall off without fruiting.

Cultivar Selection

Grow cultivars that are suitable for local conditions, so that your customer will have success in their landscape (and will return next year to buy more!). Young plant suppliers can suggest cultivars matched to your climate. Many excellent university extension bulletins are available, although most of the information is oriented towards field or homeowner use. Search the internet for a “chill hour map” for your state. The most common mistake is not matching chilling requirement to the local climate — plants with too low a chilling requirement may flower too early, resulting in low fruit set or cold damage. Plants that have too high a chilling requirement will not break dormancy for an extended period and may not fruit.

When trialing blueberries as a new crop, select cultivars that are recommended for your location and provide a range of flowering dates and plant vigor. Based on this experience, you can fine tune the planting and marketing schedule under your conditions, and narrow down to a few high-performing cultivars.

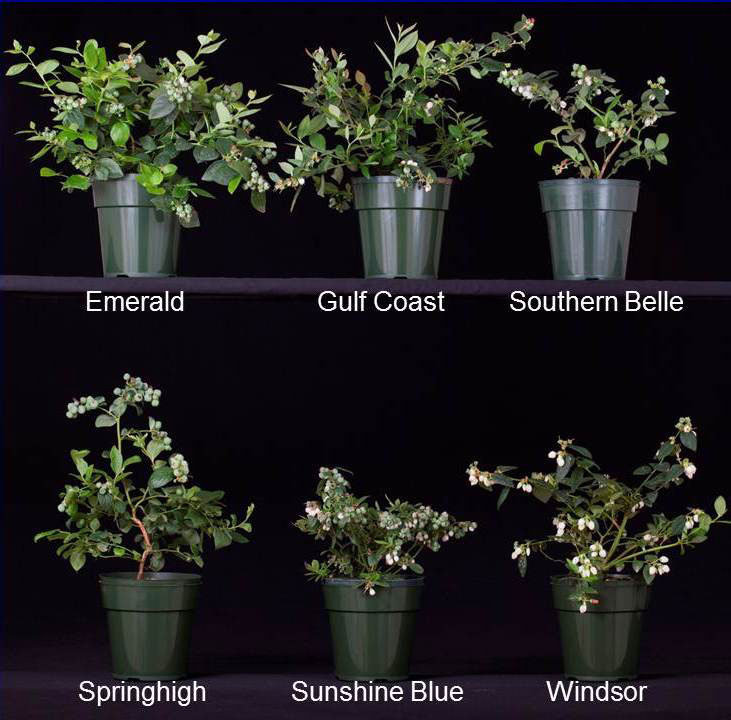

For container production, important features are strong and even branching, attractive foliage (typically small to medium leaves), resistance to disease, and profuse flowering. For landscape use and large containers, higher plant vigor is desirable. For Southern container production, use Southern highbush (Vaccinium corymbosum) cultivars (Figure 2, page 26). Based on a multi-site trial, recommendations for container-grown

cultivars in Florida include :

• ‘Emerald’ (University of Florida patent) is a

vigorous, full plant loaded with large fruit (Figure 3b, page 26) for landscape use and large containers.

• ‘Sunshine Blue’ is a well-branched, non-patented compact plant with attractive foliage, and very high number of flowers that develop from deep pink to white (Figure 3a, page 26), especially in small containers.

• ‘Gulf Coast’ is a medium-vigor, non-patented cultivar with upright form, attractive dark leaves, but lower fruit count.

For Northern locations, ‘Top Hat’ (a hybrid of northern highbush (V. corymbosum) and lowbush (V. angustifolium) have excellent characteristics, with compact growth, profuse branching, small leaves, abundant flowers and small fruit, and good fall color. Northern lowbush cultivars can work well in small containers. Other highbush/lowbush hybrids such as ‘Northcountry’ and ‘Northblue’ provide more vigorous growth for larger containers.

Market Specifications and Food Safety

Plants are more likely to have consumer interest in flower or fruit (Figure 3). The peak marketing window therefore occurs from mid-spring to early summer. The season can be extended if a mix of cultivars is grown, and research at UF is also focusing on plant culture (light, temperature, pinching) to program flowering. Consider large photo tags or printed pots for off-season sales. Aim to produce finished plants with many branches and a full canopy, with a well-established root system throughout the growing medium, free of leaf spots and other disease and pest problems, and at a similar height to other potted flowering crops (for example, 14 to 16 inches including the pot for a 1-gallon pot).

For food safety reasons (with potential liability ramifications, and also challenges in shipping), use caution if marketing with ripe fruit at retail. It is essential to follow regulations on food safety, for example avoiding contamination with E. coli or Salmonella in irrigation water, which you might not consider when growing purely ornamental crops. For more

information, refer to UF IFAS Extension guidelines at edis.ifas.ufl.edu, and other food safety guidelines available through your state extension and regulatory agencies.

Pest Management

Only apply pesticides registered for use on greenhouse/nursery blueberry plants intended for food consumption. Blueberry is susceptible to a number of leaf spot, stem and crown rot diseases, plus the usual root diseases for ornamental crops, including Pythium and Phytophthora. Typical insect issues such as fungus gnats, mites and whitefly, along with blueberry bud mite and gall midge.

Carefully check the permitted use of pesticides recommended for field production of blueberries, or for ornamental production in greenhouses. Table 1 includes some insect control strategies that are acceptable in greenhouse blueberry production in Florida. Insecticides should not impact pollinators, and biological control is both effective and desirable. For more info, refer to UF IFAS Extension document HS1156 “Florida Blueberry Integrated Pest Management Guide” by J.G. Williamson, P.F. Harmon, and O.E. Liburd, available at edis.ifas.ufl.edu, or similar guides.

Production Schedule

Blueberries are propagated from tissue culture, stem, or tip cuttings. Most growers producing container blueberries in significant numbers purchase rooted liners from an experienced, specialist propagator. Many cultivars are patented, for which propagation is restricted to licensed propagators. Non-patented options such as Sunshine Blue, Gulf Coast, and Top Hat are available if planning to propagate your own cuttings. If propagating from tip cuttings, at least 10 weeks is needed to produce a well-rooted, pinched liner. Ensure that the tip cutting is vegetative by taking cuttings from stock grown under long days (which typically means the previous summer). Tissue culture plants branch more readily than stem or tip cuttings, resulting in a more attractive plant and reducing production time in the finished container. We have not observed juvenility (resulting in delayed flowering) to be an issue for tissue culture or tip cuttings propagated in the spring and initiating flowering in the fall.

Plant from a 72-count or larger liner in June-July to finish in a 1-gallon pot the following spring. For larger pot sizes, plant in May-June with a vigorous cultivar. One plant per pot is sufficient if adequate time is allowed for pinching and establishment during the summer. Two-gallon or larger containers may require a second year of production to develop a large, well-branched plant if planting is late or with a low-vigor cultivar. Grow at 12 inches on center between 1-gallon pots during bulking up in the summer and blooming in the spring.

Alternatively, if purchasing a fast crop large liner in the spring to finish in early summer, it should have a strong root system, and be pre-chilled, well-branched, and near the final market height. I have seen pre-chilled liners sold in the spring to Northern growers as a fast spring crop, where the problem was that liners had been pruned to about 4 to 6 inches. Flower buds form on wood in the fall, so pruning liners during the winter also removes flower buds, and another year of growth would be needed for acceptable flowering.

During the bulk up phase in the summer, pinch for height control and branching approximately every six weeks as new leaves flush out, starting 4 inches above the media in a 1-gallon container (6 inches for large pot sizes) and with each pinch 1 to 2 inches above the previous pinch. When pinching, use clean clippers including a dip in

sanitizing agent between each bench or cultivar. Pinching cuts serve as an entry point for many stem (and leaf) pathogens, and a broad-spectrum fungicide may be needed at the end of each day that pruning occurs. Don’t overwater after pruning, and keep foliage dry over the following week. Maintain air circulation with fans, especially before and after pruning. Ensure foliage is dry when pruning, and avoid bruising leaves. The last pinch should ideally occur before flower initiation (short days) in the late fall, meaning that for most growers, the last pinch will be in August to September.

A typical soilless substrate with moderate to high porosity (i.e., peat and/or bark with 30 to 40 percent coarse perlite) is important to avoid Phytophthora and other root rot diseases. Blueberries are susceptible to iron deficiency and should be grown at pH 3.5 to 5.5, typically in a substrate with little or no lime added. Do not use your regular limed mix — if pH is 6 or above, plant vigor will be greatly reduced and you are likely to struggle with iron deficiency and pale color throughout the crop. Avoid overwatering while plant is getting established and during the winter dormancy and slow-growth periods. Allow media to dry between watering, but do not allow plants to severely wilt or leaf damage will occur, increasing labor needed to clean up the crop. Keep plants well hydrated under high air temperature and light. Nutrients can be supplied either in water-soluble form, with 100- to 150-ppm nitrogen with each irrigation from an acid-reaction (high ammonium) peat-lite fertilizer including chelated micronutrients during the active growing period, or a moderate rate of controlled release fertilizer incorporated or surface applied to the growing medium.

Growing under cover from the rain helps reduce leaf foliar diseases. During winter, provide protection from rabits, rodents and deer. Air movement with fans or natural ventilation is needed to avoid powdery mildew in a greenhouse. Shade is not desirable except to avoid high temperature stress, because blueberries are full-sun plants with increased flower count at high light level.

Greenhouse temperature during the establishment period (May to September) should be 70° F or higher average temperature. This bulking up can occur in available greenhouse space after spring crops are sold, or outdoors with careful attention to diseases. Blueberries accumulate chilling hours between 32 to 45° F, and plants can be moved to a high tunnel or outdoors in the fall. Plants overwinter with sub-freezing temperatures so long as plant root systems are well established and the cultivar is suited to your area. Following chilling, plants can be grown under ambient temperatures for a slower, natural flowering time, or brought into a heated greenhouse (65 to 70° F) under long days for more rapid flowering. With artificially early flowering, remember that strong fruit set only occurs in the presence of insect pollinators, and young developing buds are susceptible to freezing damage.

In Conclusion

Blueberries provide a niche crop that fits with market trends. Current retail prices are strong at around $9 for well-branched, blooming plants in 1-gallon containers. Consider adding container blueberries to your line of ornamental edible crops.

Blueberries provide a niche crop that combine consumer interest in edible gardening with sustainability and low-care perennials.

Video Library

Video Library