Microscopic menaces: Managing mite misadventures in the greenhouse

Mites are nearly invisible to the naked eye, but their impacts on commercial plant production are massive. Their diminutive size means infestations are easily overlooked until damage becomes visible — and by that point, severe. Recognizing the early symptoms of mite damage is critical for effective intervention and avoiding losses.

SCOUTING AND EARLY DETECTION

Scouting is essential for early mite detection and serves as the cornerstone of successful mite management. Because mites can be nearly microscopic, it is often necessary to scout for symptoms rather than relying on visual confirmation of the actual mite.

Identify early symptoms of mite damage, including any distinctive bronzing, stippling, mottling, speckling, webbing or unusual growth patterns that might indicate the presence of mites (Fig. 1). When scouting, inspect older leaves, buds and terminal growth — pay attention to mite-prone plants and examine the undersides of leaves to search for tiny specks (in the case of spider mites) in a variety of colors (green, red, cream, orange, brown).

For other mites that are too small for the naked eye — broad, cyclamen, eriophyid and some flat mites — the use of a 20X hand lens or dissecting microscope is critical to seeing these minute pests. Be sure to check not only the symptomatic plants but also adjacent asymptomatic ones (Fig. 2). By the time symptoms are apparent, the causal mite may have moved on to a new host. This is especially important for the smallest mite pests. Laboratory diagnosis may be needed for confirmation for tarsonemid, eriophyid and tenuipalpid mites.

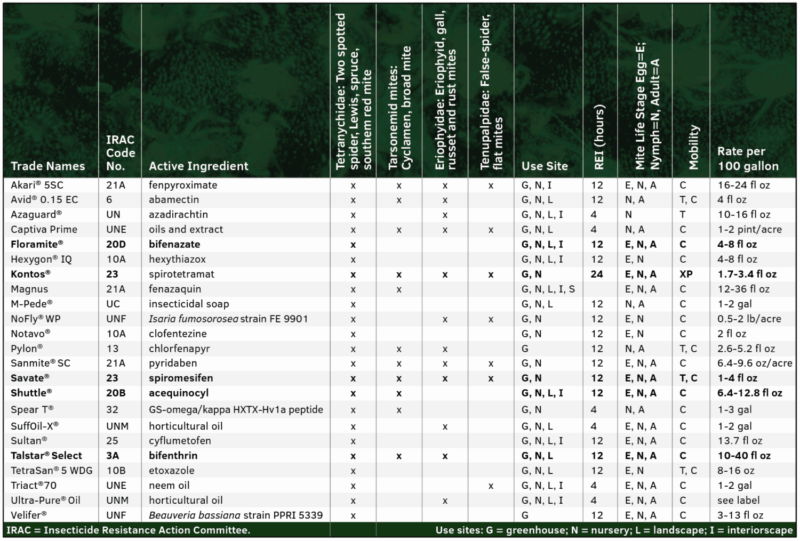

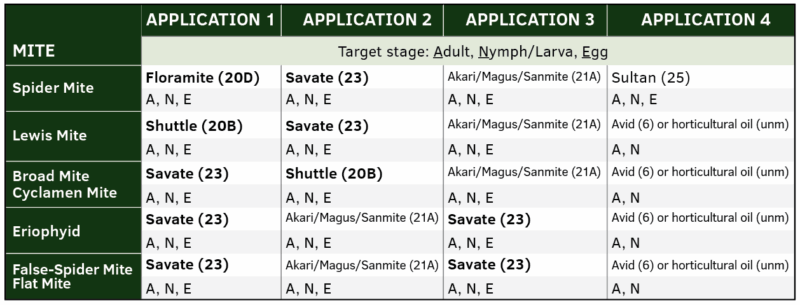

Accurate mite identification is essential. Not all miticides work on every mite species (Table 1), so knowing the specific mite involved helps in selecting the right control measures.

COMMON MITE PESTS IN GREENHOUSES, NURSERIES

Spider mites (Tentranychidae)

Spider mites, particularly the two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae), are among the most destructive mite pests (Fig. 1a). There are over 1,200 species of spider mites, including the southern red mite, spruce mite and Lewis mite (Fig. 1b).

Compared to other mite pests, adult spider mites are enormous — approximately 0.4 mm or 400 micrometers (μm) long. They appear as tiny, fast-moving spots of red, orange, brown, green or yellow that can be seen with the naked eye. Larvae have three pairs of legs, adults four pairs. Males have a pointed abdomen, females a rounded one.

For quick detection in the greenhouse, hold a white paper plate held under a branch and tap it sharply. The dislodged mites may appear as quickly moving spots against the white background.

Eggs are spherical, 150 to 350 μm in diameter and often begin as translucent, developing color (yellow, orange, light green, pink) of the surrounding leaf and becoming opaque as the mite ages.

Symptoms of damage include bronzing, stippling and, in severe cases, leaf drop and webbing.

Most mites thrive in warm, dry conditions, although the Lewis mite, southern red mite and spruce spider mite are adapted to cooler temperatures.

Thread-footed mites (Tarsonemidae)

This group includes both cyclamen mites and broad mites. Both are smaller than most spider mites, semi-transparent, with distinctive hind leg differences between males and females. Females have a long pair of threads on their back legs, while the hind legs of male mites possess a pincer-like claw.

Both broad mite and cyclamen mite prefer high humidity and to hide in buds, leaf axils and plant crevices to avoid direct sunlight. When scouting for broad or cyclamen mites, look for malformed terminal buds, flower buds and deformed, stunted growth on susceptible host plants (Fig. 3). Sparse webbing may be associated with severe broad mite infestations.

Broad mite (Polyphagotarsonemus latus)

Adults are 0.1 to 0.2 mm in size and often appear engorged. They are light yellow to orange or green, with a stripe that forks in the back. Young broad mite larvae have only three pairs of legs.

Eggs are 80 μm long, football-shaped but appear dimpled, like a golf ball with 29 to 37 opaque white spots/dimples per egg.

Broad mites are often found in spring greenhouses and shade houses feeding on:

- begonias (angel wing and Reiger)

- geranium (zonal and ivy)

- gerbera daisies

- fuchsia

- hydrangea

- New Guinea impatiens

- pittosporum

- torenia

- verbena

- and many vegetable crops.

Their toxic saliva causes curling, shortened petioles and distorted growth — symptoms that might be confused with nutrient deficiencies, herbicide injury or virus infections (Fig. 3).

Cyclamen mite (Phytonemus pallidus)

Adults are 0.2 to 0.3 mm long, translucent, salmon-colored and elliptical with four pairs of legs. Eggs are oval, smooth, whitish and 100 μm long.

Cyclamen mite infests:

- cyclamen

- African violets

- azalea

- begonia (tuberous)

- chrysanthemum

- dahlia

- delphinium/larkspur

- fuchsia

- geranium

- gloxinia

- ivy

- New Guinea impatiens

- petunia

- and snapdragon.

Symptoms of damage include flowers that discolor, shrivel and fail to open; and leaves that appear crinkled, puckered and thickened, becoming brittle or rugose.

These mites are capable of parthenogenesis (reproduction in the absence of males), which can rapidly increase infestation levels.

Eriophyid mites (Eriophyidae)

Eriophyid mites (also known as gall, blister, russet or rust mites) feed on leaves and often derive their names from the symptoms their feeding induces (e.g., pear blister mite forms blister; bald cypress rust mite turns foliage orange-brown; deformity or warts by aloe wart mite).

Eriophyid mites may induce the formation of erinea (hair-like growths), galls, bud swelling and abnormal leaf development. These effects result from the mite’s saliva, which interferes with normal plant growth regulation. Eriophyid mites are amongst the smallest of all arthropod pests but are capable of significant injury to plants, directly through feeding or as a virus vector, as in the case of rose rosette disease.

These extremely small (0.1 to 0.3 mm) mites have white to translucent, elongated, wedge-like bodies with only two pairs of legs.

Eggs are often half the size of adult eriophyid mites (50 μm) and often creamy or yellow-colored.

These mites are species specific and are commonly found on ornamental hosts including:

- aloe

- bald cypress

- coneflowers

- cottonwood/poplars

- fuchsia

- linden

- maple

- plum

- privet

- and willow.

A diagnosis of eriophyid mites is often inferred from the distinctive galls, deformity (Fig. 4) or other morphological abnormalities on the host plant and require a 20X hand lens, or preferably, a microscope, for diagnostic confirmation. Some eriophyid mites vector viruses (e.g., rose rosette disease) make it difficult to discriminate between mite versus virus damage.

Tenuipalpidae (false spider mites, flat mite)

False spider mites share a similar body shape with spider mites but are generally smaller and flatter, thus the name flat mite. They do not produce protective webs.

Common genera of false spider mites encountered in the nursery and greenhouse include Tenuipalpus, Pentamerismus mites and Brevipalpus. Outbreaks in succulent production has been a growing problem in recent years.

Often brick-red to yellow with a net-like pattern or spots on their backs. Adult mites are small (0.3 mm), flattened and have eight legs. Males are rare and females are capable of parthenogenesis.

Eggs are orange to red in color and approximately 75 μm in length.

Feeding causes scabby discoloration on the leaf undersides, premature aging and misshapen foliage on succulents, orchids, palms, privets, citrus, walnuts and many different conifers.

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT (IPM) STRATEGIES

An integrated approach to mite management minimizes reliance on chemical treatments and maximizes natural control methods.

Routine scouting helps catch infestations early. Knowing the specific mite species aids in selecting targeted and effective miticides.

Removing and destroying heavily infested plant material is crucial because mites can hide in microscopic crevices that chemicals cannot always reach.

Even if miticides “rescue” heavily infested plants, the plant will remain damaged. Remember that by the time symptoms are apparent, some mites may have moved onto new hosts, requiring the removal of symptomatic plants and adjacent asymptomatic ones that may be infested.

Predatory mites, including but not limited to Phytoseiulus, Galendromus and Neoseiulus species, feed on all stages of spider mites, tarsonemid mites and bulb mites, in addition to many insect pests. Incorporating biological controls reduces reliance on miticides but rarely eliminates their need.

When chemical control is necessary, rotate products to reduce the risk of resistance and protect beneficial organisms. Choosing products that protect natural enemies while reducing their mite pests can be a challenge, but miticides like Floramite, Hexygon, Kontos, Savate and Shuttle are less toxic to many predators (Table 1 and 2).

Multiple greenhouse and field trials have found miticide performance significantly improved by the addition of a surfactant, specifically Induce, Silwet-77 and Capsil. When using a surfactant, be sure to test a small block prior to widescale application.

Avoid overuse of chemicals that disrupt natural enemies, thereby supporting a balanced ecosystem that naturally suppresses pest populations.

Mite infestations represent a significant challenge to growers. Their small size belies the vast potential for damage, making early detection, accurate identification and an integrated management approach essential. By understanding the diverse range of mite pests and their specific behaviors, growers can implement effective strategies to minimize damage and safeguard their crops.

Video Library

Video Library