Desktop diagnostics

There are no silver bullets or magic wands in plant production or pest management, but we have a wealth of information at our fingertips and a catalog of products from which to choose. To get the best return on our investment of time, effort and money, however, we need accurate diagnosis for effective management.

Desktop diagnostics is all about looking at the plant and thinking about what you know and what the plant says to you. How do you recognize when something is wrong with your crop? How can you figure out what to do about it? How much can you do by yourself, and who can you call on for backup?

WHAT’S THE PROBLEM?

In plant problem management, the first thing we have to do is notice there is a plant problem. Once we’ve got that, we need to describe the problem so we can figure out if it is likely caused by something we humans are doing, or something like a bug or fungus. Then, get a little more specific if we can so we can pick the right management tools.

My favorite way to capture symptoms and signs is this little $7 magnifier that fits nearly any phone and has a light, so you can use it in the shadehouse, in the truck, or within the plant canopy. This can help you decide if that white fuzziness you are seeing is mealybugs or fungal mycelium, which gets you halfway to a solution — insecticide versus fungicide. Pick the wrong one at this point and you waste money while the problem grows unchecked. Pick the right one and you’ve got a good chance of managing the plant problem.

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

Although these two words are often used interchangeably, signs are evidence of the thing causing the problem — fungal mycelium, insects, frass, sooty mold or residues. Symptoms are the plant’s way of telling us something is wrong — wilting, yellowing, spots or rots. Plants have a pretty limited vocabulary, though, using the same symptoms for many different causes.

Symptoms alert us to a problem, but rarely a complete diagnosis. Kind of like a cough might be caused by allergies, a bacterial sinus infection, coronavirus or just a bit too much hot sauce on your lunch. Symptoms like yellowing or wilting might be caused by drought, flooding, fungal root rot, bacterial stem rot or larvae chewing things up inside the stem.

ABIOTIC VERSUS BIOTIC CAUSES

First off, we need to look at the big picture: when did the problem start, what does it look like across the crop and how bad is it on individual plants? This requires you to look across the whole crop as you walk into the greenhouse and scan for anything that just doesn’t look quite right. The first test of whether you are dealing with a disease or pest is to determine if it’s nearly all the plants or just a few. If it’s nearly all the plants, then the likelihood is low that it’s a disease or pest. That’s because things like bugs and fungi take time to grow their population and spread, and they are generally picky, choosing just one plant type at a time.

Next, think about timing: if it appeared over just a few days, then the likelihood is low that it’s a disease or pest, for the same reason. Things like flooding and nutrition issues may take time to show up on a scale we can notice, complicating the timing clue, but the percentage affected will still be high, guiding us toward abiotic stresses.

BUGS VERSUS DISEASE

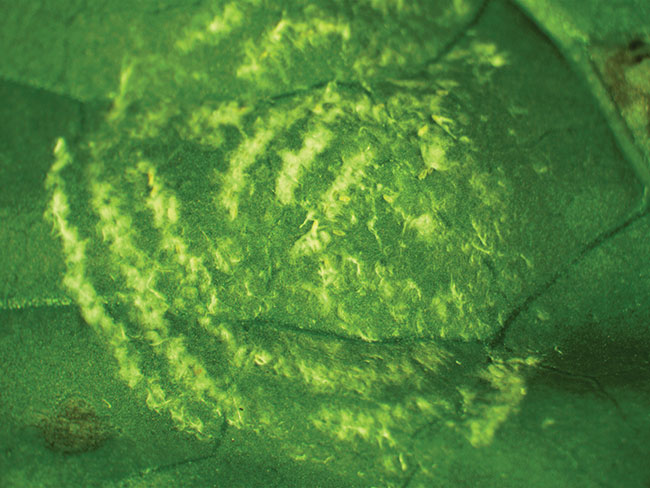

Assuming we figured out by distribution and timing that the issue is biotic, we now have to determine if it’s likely a disease problem or bug infestation. Remember when I noted that pathogens are picky — attacking one type of plant at a time usually? Well, bugs (insects and mites) may attack a few types of plants at the same time, but the symptoms will be similar across all the plants affected. With bugs, we look for insect feeding damage, leaf or flower distortion, spider mite webbing, and frass and sooty mold, which tell us insects are feeding. Here is where the zoom function on your phone or a magnifier of some sort can be really helpful.

FUNGAL, BACTERIAL OR VIRAL

Since I am a plant pathologist, I have to assume you have ruled out nutritional or other abiotic issues by timing and distribution, and you haven’t found any evidence of insect issues. That leaves us with plant diseases. To get to a management tool, we have to decide if the disease is likely viral, bacterial, or fungal. Generally, I hope it’s fungal because we have effective tools for many fungi if we catch the disease early enough, although for all diseases, prevention is the cheapest and most effective management tool.

Fungi and bacteria tend to start and spread in wet areas — places with shade, near sprinklers that keep nearby plants wetter than the rest of the crop or create splash zones, low spots, or where plants are packed together, maintaining a humid area within the canopy. Viruses often get going either sporadically throughout a seedling or transplant crop, which tends to indicate a seedborne issue, or near air intakes and doors, where insects might gain entry to a greenhouse for instance, and along traffic areas where people might touch many plants in a row.

Fungi are bullies — they can punch through major leaf veins, so they are less restricted in their growth and create round, target-like spots. They can also create tough structures that survive in soil, in pots and on benches. Bacteria are a little wimpier and wetter, so we tend to see that they cause water-soaked spots with angular edges, defined by major veins or starting at hydathodes and anywhere water collects on the plant — edges, tips and petioles.

Virus symptoms are often just weirdness — mosaic, spotty, twisted, and distorted, and often the newest growth is affected the worst, as the virus builds up in the plant.

FINDING THE RIGHT INFORMATION

The ag college in your state hires Extension faculty like me to help you find the right solution for your plant problem. Some of us also run field trials of products to ensure the products that are labeled for use at your site type are also efficacious. Labeled for use does not guarantee that it works very well.

Your Extension specialist has access to science and data where the products have been field tested under local growing conditions, to be sure that if there is a product that will work, we know how well it will work and how best to apply it, within the legal restrictions and practical constraints like budget, application technology, and supply.

CALLING FOR BACKUP

This can be a lot to sift through, so you should know about some of the folks who have your back: The National Plant Diagnostic Network is a consortium of all the university diagnostic labs across the country. Built within the U.S. university Extension system, we provide unbiased diagnosis and research-based pest management information. Clicking on your state at www.NPDN.org will take you straight to your local experts.

Accurate identification of the problem is of prime importance in effective and cost-efficient plant problem management. Most of these lab folks work closely with their crop-specific Extension specialists, keeping the experts informed about what is popping up in their crop of interest, and passing along research-based management information to the grower. This two-way street ensures we all keep headed in the same direction: healthy crops, humans and bottom lines.

Sidebar: Scouting Is Key (by Heather Machovina)

Growing outdoors comes with its ups and downs as the seasons change, but greenhouse growing is a year-round operation. This means controlling pests and diseases is also a year-round job and requires a lot of scouting. Continually scouting the crops you’re growing at various stages — whether that be when you’re taking cuttings or when it’s in a vegetative state or moving into flower — is the best way to ensure you are at the forefront of a problem, says Jeremy Wagnitz, garden to greenhouse technical manager for Certis Biologicals.

When growers know what they should be looking for and what pathogens the plants are a host for, they can catch the problem quickly and begin implementing

control measures right away.

When scouting, knowing symptoms that specific pathogens cause can help growers quickly get an idea of what they are up against, Wagnitz says. For example, if a root rot problem is spotted, understanding that the pathogen Fusarium causes half of the plant to yellow (symptom) because it moves through the vascular tissue can help. A quick look at the roots could then show mycelium growth (sign), giving the grower more information to properly diagnose the problem.

When a potential disease issue is found, send in a sample to your local university diagnostic lab to get proper identification. Knowing what pathogen you are battling will make a difference in the success of your treatment. A fungicide that works well on powdery mildew will not work on downy mildew or Pythium, Wagnitz says.

Resources are imperative to success. Plant diagnostic labs and Extension programs are a great place for information on pests and diseases. Various university professors and Extension agents have developed in-depth guides for

many crop issues, so visiting your local university can provide the best

knowledge for your specific growing area. If you want to dive even deeper

into pests and diseases, the American Phytopathological Society produces guides, called compendiums, for most crops that get very specific about the actual diseases.

Scouting on a regular basis is crucial in preventing a larger problem in your production. Pinpointing a plant that is showing disease right away and removing it from the greenhouse will prevent it from continuing to be an inoculum source for the rest of the plants, Wagnitz says. Get the problem plants out and start using preventative measures quickly to reduce the spread of disease. Continue scouting the area heavily and removing any other disease sources over the coming weeks. It’s still possible to get the issue under control even if the pathogen has spread.

Know the plants you’re growing, what the potential diseases are and when they are likely to show up during the growth cycle. Know what a healthy plant looks like so spotting abnormalities out of hundreds of similar plants becomes easier. And then, know the difference between biotic versus abiotic stressors.

For an enhanced reading experience, view this article in our digital edition by clicking here.

Video Library

Video Library